Individual Tax Series: RRSP Contributions: Maximizing Your Tax Savings and Retirement Planning

- Rylan Kaliel

- Jun 4, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Jun 20, 2025

Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSPs) offer Canadians a powerful tool for reducing taxes while saving effectively for retirement. Understanding how RRSP contributions work, their impact on your taxable income, and strategies for optimizing contributions can greatly enhance your financial planning. This blog post explores the fundamentals of RRSPs, contribution limits, and strategic considerations to maximize your tax benefits and retirement savings.

What is an RRSP?

An RRSP is a tax-advantaged savings account designed to encourage retirement savings. Contributions to an RRSP reduce your taxable income, potentially placing you in a lower tax bracket and reducing your taxes payable.

How Does an RRSP Work?

RRSPs work by investing cash that has been contributed to the RRSP and investing these in securities, such as stocks, bonds, etc. to earn income. The income earned in an RRSP is earned tax-free. When you contribute money to the RRSP, you get a deduction for the amount of your contribution. When you withdraw money from the RRSP, you pay taxes on the amount you withdraw.

One of the main questions we see is whether an RRSP is worth it. Let’s break this down into a couple of components, with the first being the tax free income portion.

Tax Free Income

Let’s assume that you contribute $100,000 into both an RRSP and a non-registered account (i.e., not an RRSP, or other similar tax-free accounts). You are conservative, so you want to earn 5% investment income each year and have a 33% tax rate. The below would illustrate the growth in each account over the next 10-years.

As we can see from the above, the RRSP earns close to an additional $24,000, due to the fact that it does not have any tax charged on the investment income. The non-registered account cannot grow as fast as a portion of the income it earns has to be spent on tax. As such, it is clear that an RRSP is superior to a non-registered account in this regard.

Deductible Contributions and Taxable Withdrawals

The other key component of an RRSP is the deductible contributions and taxable withdrawals. In theory, this should net out to being the same amount, such as follows.

If this was done in the same year, or one year after the other, the benefits would be nominal, just a timing difference between tax saved and tax paid. However, let’s consider something a bit more realistic. The first is what would happen if we had different tax rates in effect at the time of contribution versus the withdrawal (i.e., your tax rate while working may be higher than your tax rate when you retire).

As we can see, in these cases the tax savings net out to $15,000, meaning that by virtue of contributing an amount to your RRSP you saved $15,000 in taxes across your lifetime on your $100,000 contribution.

The next consideration is a bit more complicated and will pivot on combining all the concepts above.

Lifetime Growth and Deductible Contributions

Let’s say you’re debating between contributing to an RRSP or a non-registered account. You want to save for retirement, but you aren’t sure if an RRSP is worth it, after all, you’re going to get taxed when you withdraw anyways, so what’s the point? The point is what type of cash you get available to you across the entire lifetime of the RRSP.

Let’s consider a simple example, using the following facts:

You are going to invest $100,000 once and let it grow for 10-years.

You expect to earn 8% investment income in either an RRSP or a non-registered account.

You have a tax-rate of 33% at all times (at the time of contribution, growth, and withdrawal).

Any tax savings you will deposit back into the account, any tax payable you will pull from the account.

Let’s look at the RRSP first.

In an RRSP, by the end of year 9, the year before the withdrawal, we have $260,981 saved, a pretty tidy sum from our original $100,000. We’ll also notice that in year 1, we also contributed the $33,000 of tax savings from our contribution. In theory, we could also contribute the tax savings, such that there would also be a deduction for this amount, so this contribution could be larger, but let’s keep it simple for now. In year 10, we withdraw the entire amount, paying 33% tax on this amount, or $93,014 in taxes. We are left with $188,846 after everything.

Now, let’s turn to our non-registered account and see if it performs as well.

Here we see a similar story, but no initial tax savings on contribution in year 1 and ongoing taxes on our income. The impact of both reduces the amount we have contributed to the non-registered account, both from lack of tax savings and due to our income being taxed. At the end of 10 years, we are left with $164,008, which is almost $25,000 less!

The above illustrates the power of the RRSP’s tax-free income and deductible contributions. This can make an RRSP an extremely powerful tool for saving. That said, there are a few other considerations to keep in mind.

Actual Contributed Amount

While the above example contributes the tax savings to the RRSP, consider a situation where you opted to not contribute this amount. This would mean on a $100,000 investment, you have the $100,000 in an account but you also have $33,000 today to spend on bills and other important life items. Your true investment into an account is $67,000, however, you still have $100,000 in the account. This demonstrates that the actual contribution is much less than the money you are left in your account.

Annual Withdrawals and Tax Rate

The above example assumes you withdraw the entire RRSP at one point, using a 33% tax rate. Previously, we had discussed different tax rates for different years. The value of an RRSP is also the timing of the withdrawals, to which you can withdraw a different amount each year to make use of lower tax rates. Further, typically your RRSP, or Registered Retirement Income Fund (RRIF) can continue to grow during this period, with tax-free growth, meaning only what you withdraw is taxed, not the growth for that year.

Tax Credits

Earning pension income, such as amounts from an RRSP, may be eligible for tax credits that could further reduce your taxes payable. As such, it may be beneficial to consider withdrawing some amount each year to benefit from this credit, provided you meet the other requirements for the tax credit.

Employee Matching

Many employers are now offering matching RRSP contributions. This means that if you contribute, let’s say $200, the employer will also contribute $200. In the case of contributions being made, this totals $400. While the above notes that you would get a deduction for each contribution made, which in this case we would think would be $400, the actual deduction is $200.

The rationale for this is that essentially the employer provided you with $200 more cash, so in theory we should increase our income by $200 and then take a deduction for the $200 the employer contributed to our RRSP (net $0). We would then deduct our $200 we contributed and get our net deduction of $200.

When reviewing your RRSP contributions and deductions for the year, consider this concept and understand that the employer contribution may not show up explicitly as a deduction for these reasons.

Withdrawing from your RRSP

When you withdraw from your RRSP there are required tax withholdings on these withdrawals. The withholding rates are generally as follows:

10% (5% in Quebec) on amounts up to $5,000

20% (10% in Quebec) on amounts of $5,000 and over, up to and including $15,000

30% (15% in Quebec) on amounts over $15,000

As noted above, when you withdraw from your RRSP the withdrawal is treated as income. This income is included on your return and tax is calculated on this and other income. The withholdings will be treated as a reduction to your taxes payable (see our Basics of Individual Taxation blog for more details). You would only pay tax on any taxes payable in excess of the withheld amounts. For the most recent withholding tax rates, visit the CRA’s website.

There can be exceptions to the withholding tax requirements in certain cases, such as in the case of excess contributions (see Dealing with Excess Contributions below). In order to get an exception from the tax withholding requirement Form T3012A Tax Deduction Waiver on the Refund of your Unused RRSP, PRPP, or SPP Contributions from your RRSP, PRPP or SPP is required to be filed prior to any withdrawals. This form is submitted to the CRA and once approved can be submitted to the administrator of your plan to request the amounts be withdrawn without withholding taxes.

An important thing to consider is that the approval of Form T3012A by the CRA can take some time, so you may have to wait several months or even close to a year to get this approval. Be sure to consider if waiting on the approval of this form is in your best interest and discuss with a tax professional ahead of proceeding.

Getting out of withholding taxes is almost always preferable as it leaves you with more cash today. Take the following illustration as an example.

In the above case, there is withholding tax of 10% on the $5,000 withdrawal. This leaves the person with $4,500. Where there is no withholding tax applicable, they would instead get the full $5,000. For some, $500 may not seem like a lot, but if you are getting into the 30% tax rate this could be $1,500, a significant hit.

Understanding RRSP Contribution Limits

There is a specific amount you can contribute to your RRSP in a year, meaning that there is a limit on your contributions. This is known as your RRSP contribution limit. A general illustration of how your RRSP contribution limit is calculated can be seen below.

The above illustration appears complex, however, there are a few key terms to understand, which are defined below.

Earned income: Generally, this is your employment earnings, self-employment earnings, and certain other types of income, less their expenses. This is different from net income for tax purposes, as was discussed in our Basics of Individual Taxation blog.

Annual limit: This is the maximum amount your RRSP contribution limit can increase in the year. For 2024, this amount was $31,560.

Pension adjustment: These are typically amounts calculated by pension plan administrators to reflect the value of pension benefits earned in a registered pension plan (RPP).

Contributions: These are the amounts you contributed to your RRSP during the year.

Not all terms are discussed, as they are more complex and out of the scope out of the blog. The above is intended to give you more of a background on the general process of how these are calculated. Note also that the CRA clearly indicates your contribution limit on your annual Notice of Assessment (NOA).

Let’s see an illustration of this calculation in effect.

In the above example, we assume that the person had earned income of $100,000, which at 18% is $18,000. As $18,000 is less than the annual limit of $31,560, we use $18,000. Further, we have pension adjustments of $10,000, so the excess of 18% of earned income over the pension adjustments is $8,000. This increases our RRSP contribution limit. We then reduce our RRSP contribution limit for the $25,000 of contributions in the prior year, to determine our unused RRSP contribution limit, for the current year.

RRSP Deduction Limit

The RRSP deduction limit is a limit on the amount of the deduction you can get from your RRSP contributions. For most persons, this is the same amount as the RRSP contribution limit. Where differences can exist is where a person contributes an amount to their RRSP does not deduct the contributions. This will result in the RRSP contribution limit decreasing, but not the RRSP deduction limit. Instead, these contributions will be referred to as undeducted RRSP contributions, which can be deducted in future years. Often these will also be shown on your NOA.

Let’s look at an illustration of this, assuming that the RRSP contribution and deduction limit starts at $50,000, contributions of $25,000 are made, but no deductions are made in the year.

As can be seen above, the RRSP contribution room decreases, but not the RRSP deduction limit. Instead, we have a balance of $25,000 in our undeducted RRSP contributions, which can be deducted in future years.

Why Would One Not Deduct Their RRSP Contributions?

It would seem practical to deduct your RRSP contributions in the year they are made, but there may be situations where someone would want to not deduct these. Consider a situation where an individual is taking a hiatus from work and during the year their tax rate is 20%. They still have cash, so they made a $20,000 contribution to their RRSP. They know in the following year they will return to work and have a tax rate of 50%.

In the above example, we can see that the tax savings are significantly better in the year they return to work then in their hiatus year. This illustrates one of many reasons to hold off on deducting your RRSP contributions. That said, it is always advisable to discuss this type of tax planning with a tax professional.

Excess RRSP Contributions and Penalties

There are times that a person over contributes to their RRSP. Exceeding your RRSP contribution limit can lead to significant penalties, including a tax of 1% of the excess contributions per month until the amounts are withdrawn and the required filing of the Form T1-OVP Individual Tax Return for RRSP, PRPP and SPP Excess Contributions.

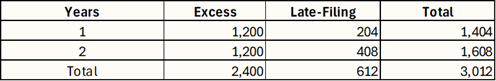

Failure to file this form on time can also result in late-filing penalty which is calculated as 5% plus an additional penalty of 1% for each month the form is outstanding and not filed after the filing deadline. This penalty can increase to 10% plus 2% for each month the form is outstanding and not filed after the filing deadline. The deadline for filing this form is March 31.

Let’s see an illustration of these penalties. Let’s assume a person has $10,000 of excess contributions outstanding over two years. Additionally, the person has not filed the Form T1-OVP for both years and is now over a year late for both years’ forms.

As we can see, these penalties can add up, in this case they are over 30% of the $10,000 of excess contributions. This illustrates why it is so important to identify these excess contributions early and ensure they are corrected as soon as possible and the required Form T1-OVP is filed on time.

One important thing to note is that for the penalties on excess contributions to apply they need to both exceed your current RRSP contribution limit plus $2,000. This means that if you have excess contributions over your current RRSP contribution limit of $1,000 you will not incur a penalty. These penalties only arising where the excess is more than $2,000.

Dealing with Excess Contributions

When dealing with excess contributions you will want to withdraw the amounts from your RRSP as soon as possible. As was discussed in Withdrawing from your RRSP, withholding tax may apply on this withdrawal. One option to avoid the withholding tax is to file the Form T3012A, which can get you out of the requirement of paying withholding taxes.

As discussed in Withdrawing from your RRSP this form can take some time, so you may have to wait for its approval. Thankfully, in many cases, the CRA has understood the time it takes for this approval and is willing to back-date the date the withdrawals were made to avoid further penalties from arising.

An alternative is to simply withdraw the amounts without filing Form T3012A. This will be subject to withholding taxes, but this may outweigh the time waiting for an approved Form T3012A. Additionally, these excess contributions may not actually be taxable.

The filing of Form T746 Calculating Your Deduction for Refund of Unused RRSP, PRPP, and SPP Contributions with your tax return may result in there being no impact to your tax return. Form T746 provides a deduction against the income on withdrawn RRSP amounts where it is for a refund of unused RRSP contributions, such as excess contributions. In effect, this will result in an income inclusion for the withdrawals but a corresponding deduction against this income.

As such, while you get less cash on a withdrawal without filing Form T3012A, this cash will be return to you with filing Form T746, resulting in you netting out to the same amount of cash in the long run. It is important to note, Form T746 should also be filed if you do file Form T3012A to avoid any taxes being payable on the withdrawn amounts.

An additional consideration may be to simply stop contributing to your RRSP and wait for the RRSP contribution room to catch up. This can be tricky as it may involve filing Form T1-OVPs for more years and you could incur significant penalties as part of this waiting process, so discussing this option with a tax professional is highly recommended.

As a general guide on the process, we would typically recommend the following flow of events in any excess contribution situation:

If there are outstanding Form T1-OVPs, file these immediately.

Consider if Form T3012A would be valuable in your case and, if so, file this immediately.

If Form T3012A is filed, then withdraw once approved, if determined not to be needed, withdraw as soon as possible.

File any additional required Form T1-OVPs.

Complete Form T746 as part of the filing of the tax return to avoid taxes payable on the withdrawal.

This process can be extremely complicated and as such, it is recommended that you consult with a tax professional throughout the process. Many of these forms can required a considerable amount of attention and careful documentation, so a tax professional’s guidance will be invaluable in the process.

Strategic RRSP Contributions and Tax Planning

Strategically timing RRSP contributions can significantly improve tax efficiency. Consider the following:

High-income years: Maximize RRSP contributions to reduce taxable income and move into lower tax brackets.

Income deferral: Contribute to your RRSP during peak earning years, withdrawing funds during retirement when typically in a lower tax bracket.

Spousal RRSP contributions: Contributing to a spouse's RRSP can help split retirement income, potentially reducing household taxes during retirement.

Special RRSP Withdrawal Programs

Certain RRSP withdrawal programs provide flexibility without immediate taxation, notably:

Home Buyers’ Plan (HBP): Allows first-time homebuyers to withdraw up to $60,000 tax-free to purchase a qualifying home, repayable within 15 years. Visit the CRA’s website for more details.

Lifelong Learning Plan (LLP): Withdraw funds tax-free up to $10,000 to finance full-time education for you or your spouse, with specific repayment conditions. Visit the CRA’s website for more details.

Documentation and Reporting Requirements

RRSP contributions are typically reported on tax slips (receipts) provided by financial institutions:

Receipts must be submitted with your tax return (or kept available if filing electronically).

Contributions made in the first 60 days of a calendar year can be deducted on the previous year's return or carried forward.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Common errors involving RRSP contributions include:

Over-contributing and incurring penalties.

Incorrect calculation or misunderstanding contribution limits.

Missing out on maximizing available RRSP room.

To avoid these pitfalls:

Regularly verify your contribution limit via CRA My Account.

Strategically time your contributions.

Maintain organized records of all RRSP receipts and contributions.

Summary

RRSP contributions are an essential part of effective tax planning and retirement preparation for Canadian taxpayers. Proper understanding, strategic planning, and accurate reporting help optimize your tax situation, build a secure retirement, and maximize your long-term financial benefits.

Stay tuned for our next blog, where we’ll discuss the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and Employment Insurance (EI) deductions.

KLV Accounting, a Calgary-based accounting firm, is here to help. Contact us today to enhance your financial strategy, minimize your taxes, and drive business success! For a free consultation, call us at 403-679-3772 or email us at info@klvaccounting.ca.

.png)

Comments